Colombian Cardiac Adventure, Part 3

If you’re an expat, you may not want to read this. If you’re considering becoming an expat, you need to read it. Here’s what I’ve taken away, thus far, from my recent heart attack, and a very real brush with death in Medellin Colombia. Some of these insights I never imagined. Some of them were almost worth the roller coaster ride and associated pain and concern they presented.

If you’re an expat, you may not want to read this. If you’re considering becoming an expat, you need to read it. Here’s what I’ve taken away, thus far, from my recent heart attack, and a very real brush with death in Medellin Colombia. Some of these insights I never imagined. Some of them were almost worth the roller coaster ride and associated pain and concern they presented. We expats pride ourselves on our resourcefulness, our resilience, and our spirit of adventure. We tend to be dismissive of folks who stay behind in their comfortable, familiar surroundings. We consider them fearful, overly cautious, lacking in imagination and wanderlust. We recite the old chestnut that ‘life begins at the end of your comfort zone.’ Well, I’ve come to understand that death may begin there, too.

In some ways, we expat types are our own worst enemies. We ignore danger, boasting of our treks to far-flung and exotic locales, lifting several brews to ourselves after a particularly harrowing adventure. Today’s expatriates are, after all, baby boomers, mostly, so we’re never going to get old, or decrepit, or god forbid ill. Boomers, not Buddhists, we push the envelope all the time, never satisfied with what is, but what could be. We take chances we probably shouldn’t. And we do this in many cases without the cover and concealment of robust health care coverage and emergency rescue support.

Here’s one reason we need to exercise more caution. My situation is likely common among expats. Mariah is twelve years younger than me. So any decisions I make, any adventurous initiative I embark upon has real, and potentially devastating consequences for her. If I’d died on the ER cot that night, not only would my wife have lost me and the companionship I offer her, plus the protection and support I provide in a foreign land, she would have lost half our income as well. I was being selfishly naïve in my assumptions about this. As it is, with every protocol and procedure now, every drug assignment and dosage, and the pending cardiac rehab, all of these are framed in a new way. As mercenary as it may sound, my spouse and I are together protecting her investment, by assuring my continued health.

And here’s the thing: Death isn’t the major factor. Disability is. If I’d died that night, the legal and logistical path for her would have been perilous and confusing to be sure. But once she’d navigated those immediate issues, once she’d taken care of the paperwork, and then figured out what to do with my lifeless carcass, the rest would be relatively easy. She’d collect whatever residual funds remained, and move on with her life. But if I’d become disabled, unable to care for myself, limited in my movements and/or abilities, I’m quite frankly not sure what she would have done.

Here’s advice for those couples thinking of expatriation. If you’re already best friends one of two things will happen. You’ll either lose that powerful connection due to the stresses and strains of assimilating to a new environment, or your bond will become stronger because of it. If you’re not already best friends, you will not become so by moving to a foreign land. Trying to assimilate to a new culture is hard, demanding work. It’s not just the language challenge, though that is daunting. It’s the nuance, the uncertainty, and the flood of unknowns that come at you day after day. It’s the maddening attempts to navigate the bureaucracy of your adoptive country. It’s the confusing way people drive, and shop, and greet one another, and the laughable missteps you’ll make as a foreigner. It’s the stress of trying to make it all work.

This leads me to the last comment: What did cause my heart attack? As I said, I was not a candidate. With my cardiac profile, no one would have predicted I’d end up in that ER with a myocardial infarction. My supposition is that it was stress. Think about it: In the previous two years, my wife and I had upended our comfortable lives in Ohio, decided to move offshore, and begun the necessary steps for that. We’d given away, sold, or discarded acquired material things. We’d found a tenant for our condo. We’d researched what we thought we needed to make the move, in our case to Panama the first time. We traveled there to check into it, and then returned assured that Boquete was the place for us. We condensed our belongings into five suitcases, bought airline tickets, and said goodbye to dear friends. Then we left the U.S., and all the ease and comfort we’d been accustomed to.

But Boquete was not ‘the place’ for us, as it turned out. We discovered Medellin, returned to Panama, and went through the same exercise all over again. Sell, discard, give away, pack, say goodbye, etc. etc. By the time we entered the apartment we now occupy we’d lived in six different dwellings in eighteen months. That’s a new home every three months. And that means a great deal of stress.

So here’s what I advise. If you’re considering leaving your comfy, easy life behind and becoming an expatriate, ask yourself why? To misquote a president we boomers identify with, ‘ask not what your country can do for you; ask why you’re leaving your country.’ Why are you doing that? Can’t afford to live in the U.S. anymore? I get that. Tired of the constant clash and clang of the current political climate? I get that, too. Just want to try something different? Okay, I’m with you. My wife and I had all those motivations, and more. One of them was to reduce our stress level. Well, that seems not to have worked.

This piece seems to be a warning to stay put, but I’d never advise anyone to do that. We love living in Colombia, and I can’t imagine leaving Medellin, except maybe feet first. Which is how I almost did.

What I’m saying is that there’s a lot of stress and strain involved in leaving one’s comfort zone, more than we anticipated, and the real health ramifications of that are something many potential expats may not consider.

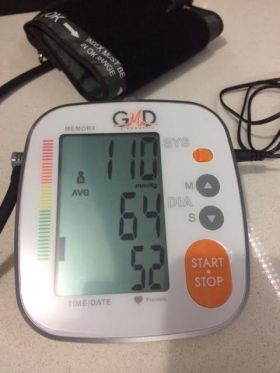

By the way, I’m well on the road to recovery, and determined to lower my stress level by whatever means necessary. It’s already started; I’m spending a lot less time in front of a computer these days. So if I go dark for a while, that’s the reason.

I referred to the metaphysical aspect of my cardiac adventure, and here it is. Warning: this may sound a bit airey-fairey, loony-tooney, but it’s what I felt at the time, so I’ll share it. Lying on that ER cot with my heart fluttering and flailing I really was waiting for each and every beat to arrive. Flat on my back, staring at that bright overhead light was much more than metaphor; it truly cast a new light on my existence as a man, a husband, a father, a grandfather. I saw that I’d been waiting for the wrong things for a very long time, that I’d been taking a lot for granted that may not be worth waiting for.

We talk about our next adventure, the train trip to Bogotá next week, the trek back to the States in May, the trip to the Galapagos next month. We say we gotta repaint the condo next year, visit Paris within five years, maybe take the Orient Express after that. In other words, we take for granted that next week, next month, and next year are available to us without question. But the reality is that even that next heartbeat is not guaranteed. And the time between those beats is very small, I can attest. Lying there counting the beats, anticipating the next and the next, I understood this like never before: If we can somehow focus on that small amount of time, the time between heartbeats, we’ll add a vast amount of understanding to our lives. If we pour our energy into that almost infinitely small space of time, our lives can be richer, and much more rewarding. That next heartbeat is never a given, never guaranteed. The time between beats contains a world of insight and wisdom, if we take the time to study it. When someone dies unexpectedly, people say ‘wow, he seemed so healthy, so full of life, what happened’? We question death’s visit to friends as ‘out of the blue,’ or ‘never saw it coming.’ Waiting for the next heartbeat that day, I heard my friends saying those very things. I was fortunate to come back with this message. I won’t assume again. Every fraction of a second is precious. Discern what’s really important, and focus on that time, not the frivolous and frantic.

Thanks for reading, and take care of yourselves, your partner depends on it.

Links to stories in this sequence: